Real-time integration of linguistic and non-linguistic information

In the recent decades, many researchers investigated the role of real-world knowledge in sentence processing (Altmann & Kamide, 1999; 2007; Chambers et al., 2002; Kamide et al., 2003 among many others), and the research trend was part of efforts to present alternatives (roles of contexts, frequency of syntactic subcategorizations, semantic effects, prosody, visual contexts, and real-world knowledge) to theories in which syntactic information was assumed to be prioritized by parsers (Chomsky, 1965, 1981; Frazier, 1979, 1987).

In second language sentence processing, real-world knowledge may play a different role from that in first language sentence processing due to its availability at the time of language acquisition. My new article (Ahn, 2021b) tested the hypothesis that L2 speakers' attemtps to minimize sentence processing costs could be a cause of discrepancies between L1 and L2 acquisition. Below is a brief summary of the two experiments in the article.

Experiment 1: Definiteness only

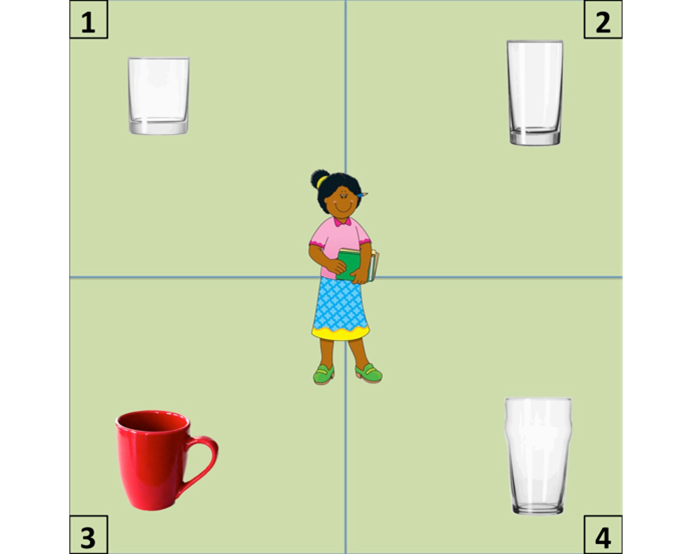

Now, consider Figure A. If you hear the incomplete sentence in 1 in the visual scene, which word would you predict the sentence would end with? There is no clear relationship between the person in the center and the objects in the four corners. That is, there is no real-world knowledge involved in Experiment 1.

-

- The woman will want to buy the...

- The woman will want to buy a...

Experiment 2: Integration of definiteness and real-world knowledge

Now, consider Figure B alongside the auditory stimuli in 2 and 3. In this case, the doctor in the center guides your attention to the stethoscope rather than the laptops based on your real-world knowledge. In addition, the auditory stimuli also provide information with regard to the (in)definiteness of the noun phrase.

-

- The man will want to use the stethoscope.

- The man will want to use a stethoscope.

-

- The man will want to use the laptop.

- The man will want to use a laptop.

What is really interestng is advanced L2 speakers' behavior. They could use definiteness information to their advantage only when the sentence did not provide usable real-world knowledge. That is, when the sentence ended with 'stethoscope,' they did not make active use of articles to predict a referent; however, when the sentence ended with 'laptop,' they reacted faster to the grammatical sentence (3b) than to the ungrammatical counterpart (3a).

Implications

The results were interpreted such that discrepancies between L1 and L2 acquisition might come from the availability of real-world knowledge at the time of acquisition. L1 children develop their language and their understanding of their surroundings at the same time, which means they acquire their grammar in the absence of real-world knowledge whereas L2 speakers have relatively more knowledge about their surroundings by the time they acquire their second language. Then, paying attention to what they already know about the relationship between the given sentence and the situation is a much more parsimonious way than to paying attention to subtle linguistic cues. In brief, L2 developmental trajectory could be guided by their efforts to streamline the cognitive processes in sentence processing.

References

- Ahn, H. (2021a). From Interlanguage grammar to target grammar in L2 processing of definiteness as uniqueness. Second Language Research, 37(1), 91-119. Link

- Ahn, H. (2021b). L2 Processing of Linguistic and Nonlinguistic Information. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 1-29. Link

- Altmann, G. T., & Kamide, Y. (1999). Incremental interpretation at verbs: restricting the domain of subsequent reference. Cognition, 73(3), 247–264.

- Altmann, G. T. M., & Kamide, Y. (2007). The real-time mediation of visual attention by language and world knowledge: Linking anticipatory (and other) eye movements to linguistic processing. J Mem Lang, 57(4), 502-518. Link

- Chambers, C. G., Tanenhaus, M. K., Eberhard, K. M., Filip, H., & Carlson, G. N. (2002). Circumscribing Referential Domains during Real-Time Language Comprehension. J Mem Lang, 47(1), 30-49. Link

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. MIT Press.

- Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on government and binding. Foris Publications.

- Frazier, L. (1979). On comprehending sentences: Syntactic parsing strategies. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Connecticut. West Bend, IN: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

- Frazier, L. (1987). Sentence Processing: A Tutorial Review. In M. Coltheart (Ed.), Attention and Performance XII (pp. 559-586). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kamide, Y., Altmann, G. T. M., & Haywood, S. L. (2003). The time-course of prediction in incremental sentence processing: Evidence from anticipatory eye movements. J Mem Lang, 49(1), 133-156. Link